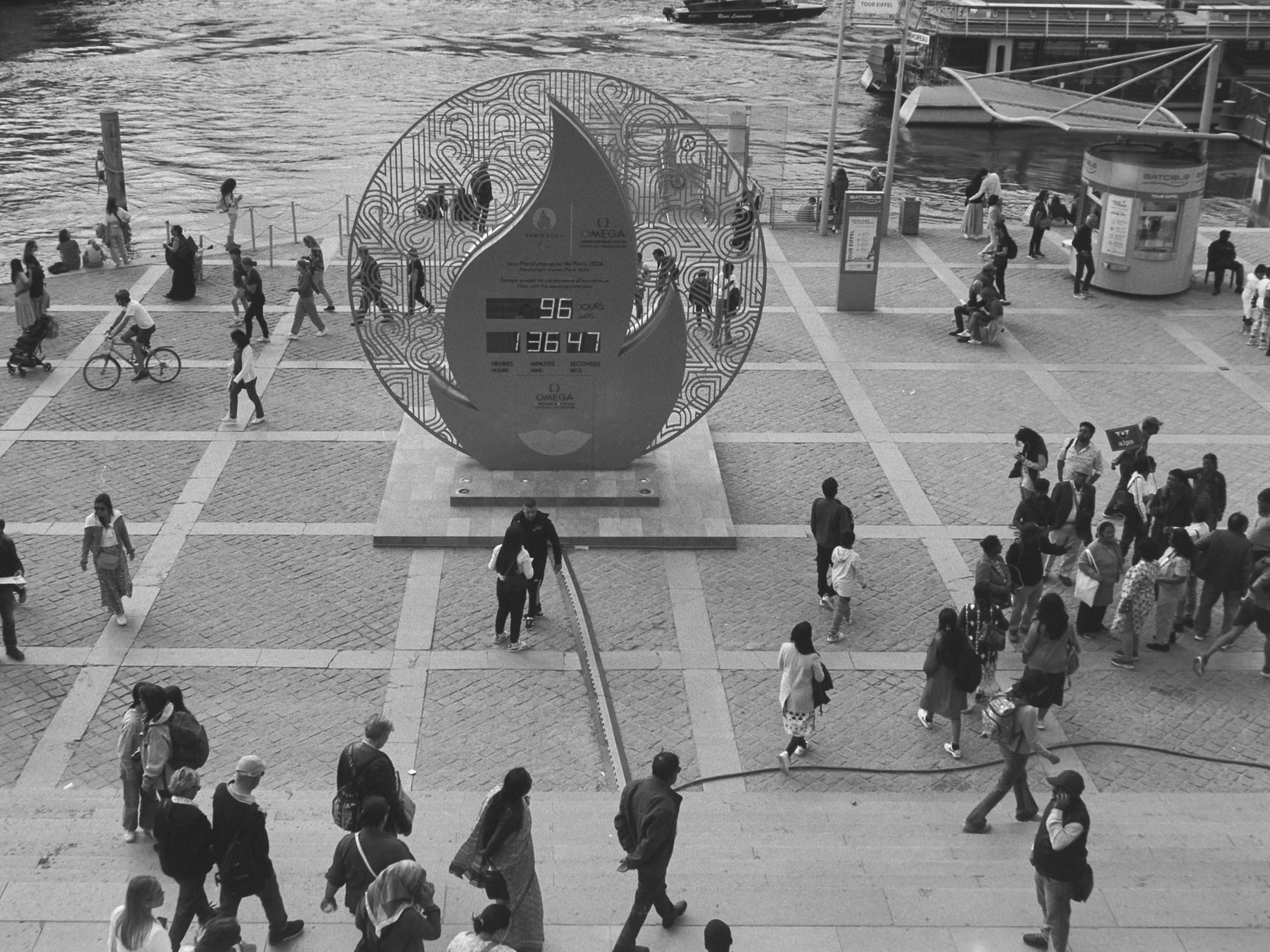

I’m writing on an absent photograph, a picture Jacques never took, which does not exist, or exists only in my head or somewhere I know nothing about, and which tells me the following story. No connection with any of Jacques’s photos for this text. Yet, since the rule of our game is that I write from one of his black-and-white photographs, after writing the text, I pick a picture, one that has nothing to do with the text, unlike what I’ve done so far – though there must be some link since I choose it, even if I know nothing about it.

And as if to breach our rule twice, I choose a picture which seems to combine two different techniques, as if Jacques had superimposed streaks of color on a black-and white, possibly false-white and false-gray, photograph.

Here is the story, untethered from any photographic inspiration.

“So you eventually came back from North America, after spending 15 years there, even if the idea of coming back to any place is alien to you; you never ‘come back’ because you acknowledge no fixed place of origin. As your mother, I know your logics, your home is nowhere and everywhere; and now you’re going - where are you going? I don’t know – ahead, yes that’s it, you’re going ahead.

But I died before you came back, believing you’d never come back after you’d spent five full years away from this country, our country, France, the country were you were born, for the first year, then the second year you spent abroad, I’d hoped you’d come back,

year after year, my hopes diminished,

year after year, my hopes diminished,

after the fifth year – allegedly a point of no return for expatriates – every time you were about to leave after your short visit, no longer than a few days, I would ask you the same question, out of habit, and also out of despair, without really expecting an answer, Will you ever come back? I couldn’t help asking you the question that had no answer, but you’d always try to give me one, albeit evasive, “I don’t know, we’ll see”, or else “we’re not sure, we’re thinking about it” - never more precise, but never definite either about never coming back. In your hesitating, there must have been a sliver of truth since you did eventually come back, I dare use the phrase ‘come back’, even if you never use it, even if you’re not coming back to your home country but to a neighboring country; it’s better than nothing and I would have felt glad, knowing I could take the train and reach out to you on the same day,

but to be fair, I never knew what your true desire was, staying, coming back.

but to be fair, I never knew what your true desire was, staying, coming back.

Your friends - you, his friends over there, you’ve kept him for yourselves, him and his family, for fifteen years, adding one more year every year, did you ever think that when he was about to leave for several long months after the few days he’d spent with me, I would watch him going up the stairs to the railway platform; the train would come, leave, taking him away to the airport; I would stay at the bottom of the stairs, sad, so sad, and he pretended to think I was not -

at the top of the stairs, he’d always turn round and wave to me before disappearing quickly, taking my sadness away with him, probably doing his best to move on, go ahead, otherwise he’d have walked down the stairs again, taken me in his arms; but he never did, he’d have been afraid of the sorrow he’d create, afraid of saying “I really can’t leave you like that” and I didn’t want him to see me in such a state. The train arrived, left, taking him to the airport; I would stay a long while at the bottom of the stairs, motionless, paralyzed, silent; I’d need some time before I could go back to my car - imagine, I hold no resentment against you, his friends who are dear to my heart, but imagine how I felt.

at the top of the stairs, he’d always turn round and wave to me before disappearing quickly, taking my sadness away with him, probably doing his best to move on, go ahead, otherwise he’d have walked down the stairs again, taken me in his arms; but he never did, he’d have been afraid of the sorrow he’d create, afraid of saying “I really can’t leave you like that” and I didn’t want him to see me in such a state. The train arrived, left, taking him to the airport; I would stay a long while at the bottom of the stairs, motionless, paralyzed, silent; I’d need some time before I could go back to my car - imagine, I hold no resentment against you, his friends who are dear to my heart, but imagine how I felt.

During the long months following his short stay at my house, knowing there was no chance he’d come back before the next planned visit, we would call each other, every Saturday without fail, morning for him, afternoon for me, six time-zones apart; we would call with metronomic regularity, and after a few years of this routine, even if we didn’t say it, we’d feel the frustration at the end of our conversations – fifteen minutes, hardly anymore; I would try to hold on even if we had nothing more to say about the past week, the conversation would go in wistful circles, I could perceive his intonation change, I could hear his desire to put an end to our talk in the way he’d repeat “well, well”,

You, his friends from over there, I don’t blame you, nor him either, not at all, but it wasn’t easy, you can believe me - and so, when he leaves after his short visit to you after one year spent on another continent, when he leaves after only a few days, when he leaves for some time, do not try to hold him back, help him to his plane, make it easy for him, do not voice regrets, even if you’ll feel some and will blame him for leaving so soon, inevitably,

nurture your relations with care, I trust you’ll invent new ways to connect, be creative, be as imaginative as we’ve been over those fifteen years, tame the distance - to be perfectly honest with you, whenever we were together, those were happy days: Christmas, the summers spent together in the South, or when he showed up for my birthday as a surprise.

You, his friends from over there - I never asked to live close to him, as our ancestors did, with all the generations sharing the same house in the same town; I never wished for that.

You, his friends, listen to me yet a little while - I’m not complaining, at least we managed to keep our relation rich and alive, but because he’d only come once or twice every year, I found it difficult to let him go, I would never have enough of him.

I can’t say it was easy for me that he was living so far away with his family, even if, as he’d remark “It could have been worse, your neighbors’ children live in Australia!”

But in spite of all my efforts, it was sometimes difficult to keep my sense of balance.

You, his friends, listen to me yet a little while - I’m not complaining, at least we managed to keep our relation rich and alive, but because he’d only come once or twice every year, I found it difficult to let him go, I would never have enough of him.

I can’t say it was easy for me that he was living so far away with his family, even if, as he’d remark “It could have been worse, your neighbors’ children live in Australia!”

But in spite of all my efforts, it was sometimes difficult to keep my sense of balance.

You, my son’s friends, I spent some time with you, I do know you’re good company for him, so, when you’re together, put your heart and soul into it, and may be, hopefully, you, and he too, will converse with the living while they’re alive, converse with your beloved ones while it’s possible, now, so that you won’t regret not having done so while there still was time; do not hesitate to show your tenderness, your love, take them beyond their limits - I’d like to tell you something I never told him, as a piece of advice, even if it’s easier said than done, do not hold back, go beyond your limits, I’m telling you this as one who never managed to do so, climb over your walls, reach out to the other side.

From my heart, I hope you’ll find a way.

To you his friends, and you my son, this is what I had to say – I think this is it, at least for the time being.”

To you his friends, and you my son, this is what I had to say – I think this is it, at least for the time being.”

The picture my hand picked was taken in New York, not far from where my mother lived, not far from where I lived as a child,

it must therefore bear some connection with this story since it is my mother who speaks in it, since New York structured our relation and never let me go - I came back to live north of New York, admittedly in another country, Canada, Montreal, I spent fifteen years there, only six hours away from New York City.

New York, like some other cities where I lived, Montreal, Paris, haunts me; I almost forgot Lyon, but Lyon haunts me less than Paris, Montreal or New York - those cities, which I left at some point, have never left me; at some point, I’ve always come back to them in various ways, going there, writing about them, looking at photographs of them, dreaming about them too. Forgetting about my cities, going ahead. No way. Moving ahead with my cities, yes, but whereto? Concretely, I move to where I live, to where I write.

it must therefore bear some connection with this story since it is my mother who speaks in it, since New York structured our relation and never let me go - I came back to live north of New York, admittedly in another country, Canada, Montreal, I spent fifteen years there, only six hours away from New York City.

New York, like some other cities where I lived, Montreal, Paris, haunts me; I almost forgot Lyon, but Lyon haunts me less than Paris, Montreal or New York - those cities, which I left at some point, have never left me; at some point, I’ve always come back to them in various ways, going there, writing about them, looking at photographs of them, dreaming about them too. Forgetting about my cities, going ahead. No way. Moving ahead with my cities, yes, but whereto? Concretely, I move to where I live, to where I write.

Paris, Montreal, Paris, New York,

Paris. Somewhere in Paris, not far from where she lived, Jacques took this other photograph: someone walks up an endless flight of stairs without even looking back to the person who, out of frame at the bottom of the steps, is watching him leave. The time between them is up, but he’ll come back, he told her, he’ll soon be back, it’s a promise: