Planting Trees.

It took me some time to figure out what seized me in the photograph. Facing this bare tree standing alone, radically alone, holding its ground against the winds, arm, hand and finger erect, pointing, pointing out to me that my quest is the exact opposite of the isolation and loneliness foregrounded in the photograph.

I’m looking for a photograph that doesn’t exist. A photograph with people holding each other around the waist, people looking into each other’s eyes, people who care, people who love.

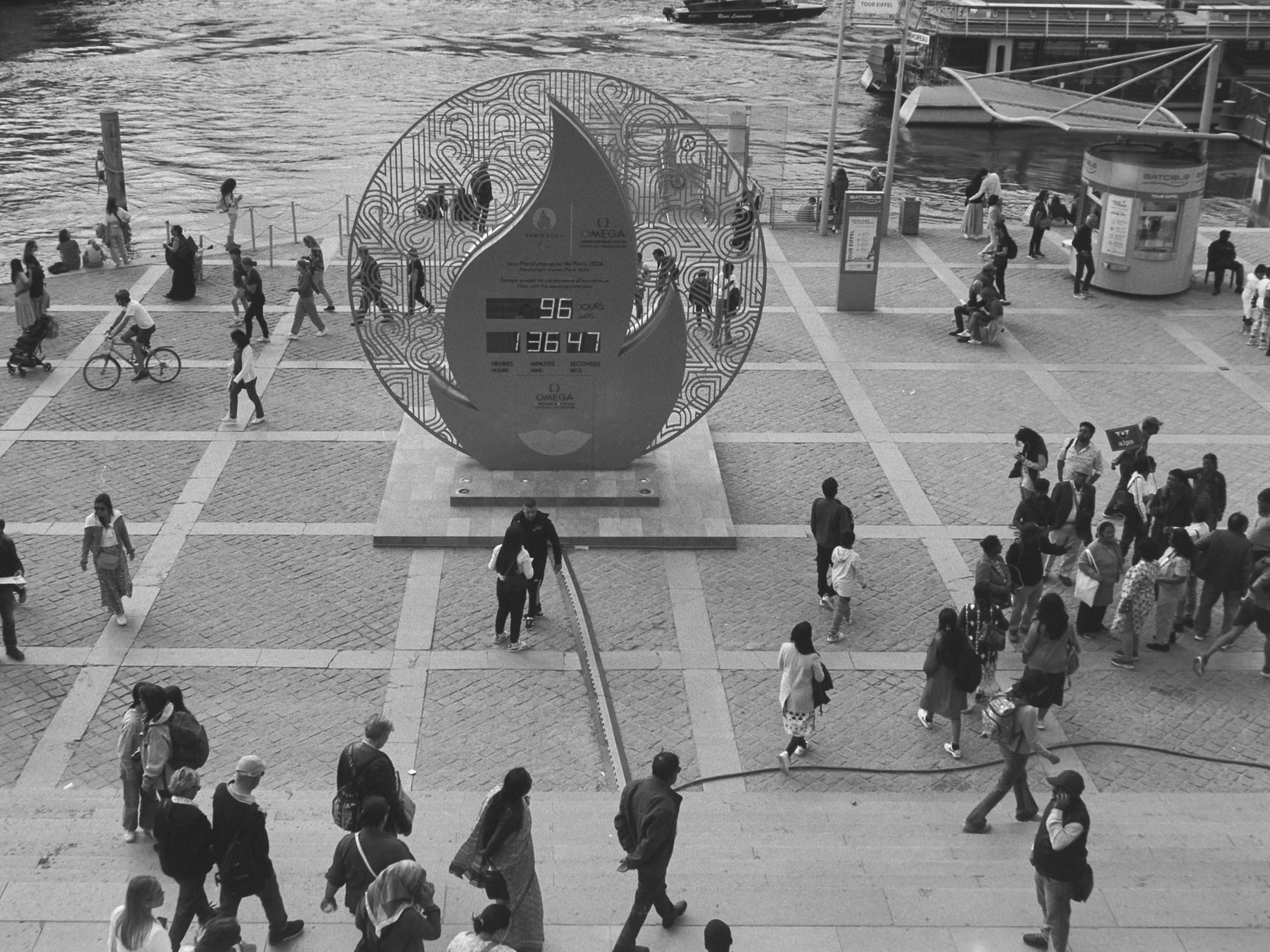

I’m not looking for a picture of social isolation. What was it that struck Jacques, made him pull his camera out, focus on the tree, frame the shot, press the shutter and include this photograph in his collection entitled “Hautes Alpes”?

The photograph which is not to be found in Jacques’s public collections does exist in an envelope, tucked away on the bookshelf behind me. It’s a photograph he took on one of our meetings by the shores of Lake Annecy. A black and white, analog silver-gelatin print - a technique as old as the tree itself, and which present-day photographers, Jacques included, find renewed interest in. The process takes time. He gives me the photo many weeks later, developed and set on paper. A photograph with the two of us standing against a backdrop of mountains – the furthest peak dusted with snow, its base masked by a first line of hills dense with trees, a multitude of trees. They are so close that their roots intertwine in an underground network keeping them connected. The very opposite of the isolated (I almost wrote desolated) tree – an echo to what I cherish, trees bound together, supporting each other, tree solidarity.

Out of frame, C. who shares his life, takes the picture. Inside the frame, S. who shares mine, has her arm on my shoulder.

A simple snapshot, a keepsake; a photograph of friendship and love, of love and friendship.

A simple snapshot, a keepsake; a photograph of friendship and love, of love and friendship.

The skeleton tree, with its horizontal main branch and its two vertical limbs, one short, the other long, challenges nature and gravity. It spurs me to give it a voice: “Once, I was loved by a shepherd and his flock of sheep, by his dog too. Long ago – they would rest against me. They cared for me, they talked to me. Animals and humans would tell me their sorrows and their joys. Then, they deserted for economic reasons, the ones went to the slaughterhouse, the others moved to cities”. Same old story of the last century.

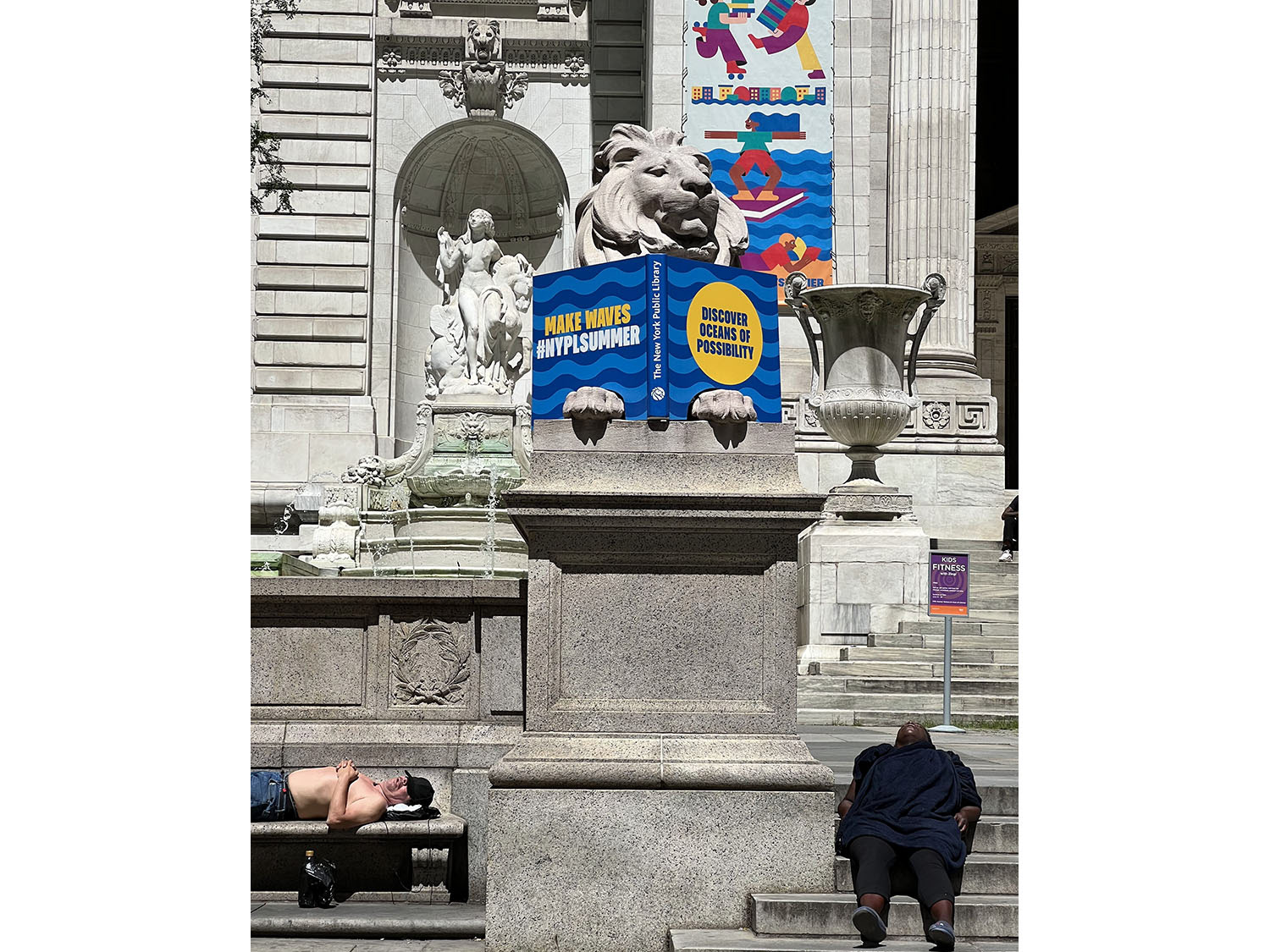

Above all, not to freeze, not to take the posture of the tree with its naked branches, facing the world alone - the fate of so many people as they grow old.

Still, it stands; hope still remains; it might escape its fate should someone come and plant trees. Just as in Jean Giono’s 1953 novella The Man Who Planted Trees. As in Wim Wenders’s 2014 movie, The Salt of the Earth, where photographer Sebastião Salgado helps restore the forests of his childhood region.

This is precisely what the photograph of the tree has conjured up – the struggle against loss. An intimate concern which has been rekindled as I moved continents once more, from North America to Europe, just a year ago. Since then, ties across the Atlantic have changed, some loosening, others tightening. No matter how I fight it, I know it too well; it’s a daunting mechanism and I’m not getting used to it. I wish I could write these shifts are external forces beyond our control, but that’s not entirely true. I am largely responsible since I’m the one imposing distance. (There is one exception though; my friendship with Allan ignores geography and in spite of ourselves being nine thousand kilometers and nine time zones apart, our conversations remain fruitful.)

Cultivating ways to live out friendship – that’s what Jacques and I are doing here, dovetailing his photographs with the texts I write from them. Inventing, re-inventing new bonds between us; a priority with some friends, provided we share desire to do so. Just like planting trees.